The initial Flashbots reference builder version started with a straightforward implementation. The implementation was a fork of geth and would behave the same way; the mempool was a ‘standard’ implementation. Additional RPC endpoints were added to allow private order flow.

The builder constructed a block every two seconds using a naive strategy; searcher bundles and mempool transactions were merged to create a block. Once the block was built and simulated, it was submitted to a relay for auctioning.

I suspect the assumption at this point was that private order flow would dominate the auction landscape and that OTC deals for order flow would be the deciding factor.

The path to optimisation

Whilst private deals for order flow may tip the balance of power in some cases, some fairly obvious optimisations could be done to increase a block builder’s win rate and were no-doubt implemented by many block builders.

Arms Race

You could throw hardware at the problem. Increasing the frequency you build blocks will undoubtedly increase the chances of winning an auction. Changing the value of when to build a block to be every second instead of every two seconds would mean that you would pick up more transactions towards the end of the block. Taking this to its logical conclusion, you would maximise the number of block submissions by throwing hardware at the problem to further increase the number of combinations.

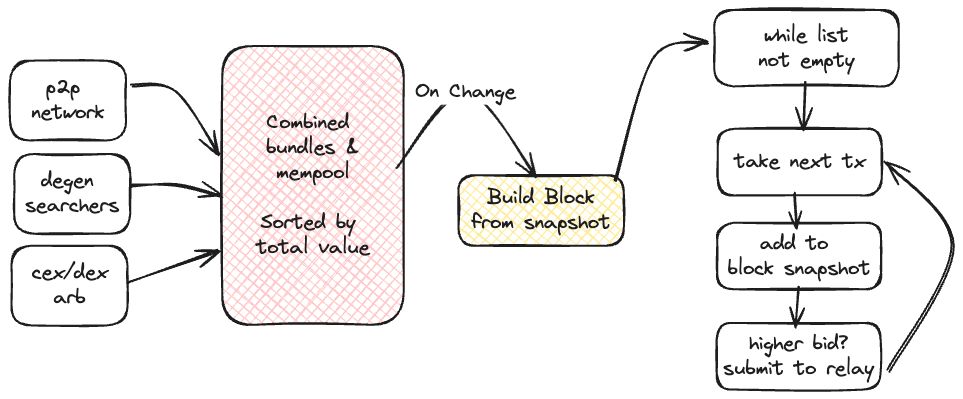

Hypothetical Block Builder Pipeline

Let’s imagine we have unlimited resources. How would you create a pipeline that builds blocks? I would build and submit a block to a relay for every transaction that entered the combined pool. This means that you would submit one hundred blocks for a block containing one hundred transactions. With each new transaction that enters the pool, you will run the process again.

Block builders don’t have unlimited resources, so the ones that optimise their pipelines to remove simulation duplication and increase throughput will likely dominate.

Wait & Check Optimisation

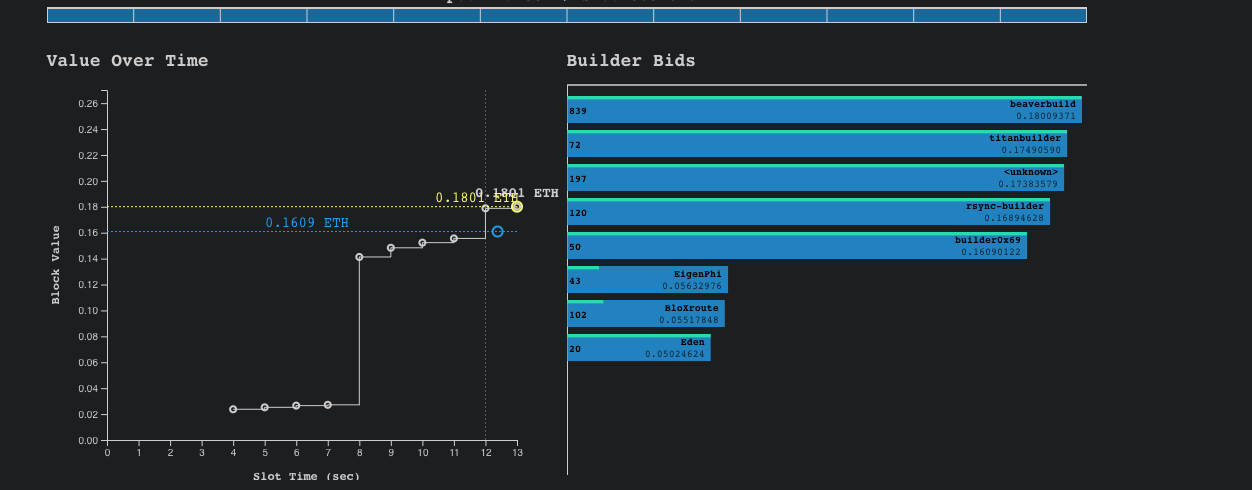

The first thing I would do is wait until the end of the block before I even submit to a relay. Then, I would progressively try to build a better block and continue to submit that. You can think of the first submission as a floor bid and the rest of the submissions as high-frequency bidding. We can see that this is exactly what the top builders are doing.

https://payload.de/data/19482327/

In this auction, the major block builders have all submitted bids by 11s into the slot but not before 8s. You can see that builder0x69 and Titan submitted bids before 9s. Beaver and Rsync will start submitting bids at or around the 10s mark. In the dying seconds of the auction, Beaver and Rsync submit 100s of progressively higher bids than the last. We can see that Beaver submitted 839 bids in total, most of them after 11s. In the last 2 seconds of the auction, they submitted over 200 bids per second. That would imply that the total number of block simulations they are doing must be greater than that. An order of magnitude higher would not surprise me.

Capitalist Relays

The PBS auction is designed to sacrifice all else in favour of price; it is a classic English auction with no other parameters considered. Whilst some may consider optimistic relays to have a major impact on latency games, I do not believe this will impact the auction mechanism for any particular player. If the validator is connected to an optimistic relay, they will increase their profits due to latency games played by block builders; if they are only connected to a regulated relay, the validator profits will be reduced. The main thing to note is that the players playing latency games are block builders and are constrained by the same limitations of the relay to which the validator is connected. The regulated relay will be slower because it needs to simulate the block, but it should be slower for all parties; the critical assumption is that the relay is honest, runs a fair auction and simulates all bids equally.

Sacrificial Block Space

In my previous blog post1, we explored situations where transactions were not included in a block when they were valid. Whilst my initial assumption was latency jitters, I suspect that what’s happening is just a race to the bottom for execution quality and block space utilisation in the name of profit.

Thinking about our simple event-based architecture

We can assume that we’ve already submitted a bid for a block at 0.09 eth with the following transactions that contain no mev and are transparently priced using priority fees only.

| tx | effective gas tip |

|---|---|

| tx1 | 0.05 |

| tx2 | 0.02 |

| tx3 | 0.01 |

| tx4 | 0.005 |

| tx5 | 0.003 |

| tx6 | 0.002 |

Let’s say a new transaction arrives in our mempool very close to the end of the auction.

| block bid 1 | 0.1 |

|---|---|

| tx | effective gas tip |

| tx0 | 0.1 |

We then submit a bid (0.1) with just that transaction in the block as it is higher than our previous bid (0.09). We then progressively add transactions to the block and submit those bids.

| block bid 2 | 0.15 |

|---|---|

| tx | effective gas tip |

| tx0 | 0.1 |

| tx1 | 0.05 |

| block bid 3 | 0.17 |

|---|---|

| tx | effective gas tip |

| tx0 | 0.1 |

| tx1 | 0.05 |

| tx2 | 0.02 |

etc

When we submit these bids, the first two land in the auction in time, and the third one doesn’t. Consequently, we’ve “removed” perfectly valid transactions from a block in favour of higher-paying transactions because we couldn’t build a block fast enough. Note, there is no mev at play here. We have sacrificed block space utilisation for priority fee profit.

Let’s remove PBS from the equation for a second; a solo validator running a similar optimised block-building algorithm would produce the same result. The proposer would continuously build blocks, hold the best result in the cache, and then flush it for propagation when deemed appropriate.

Time is money

Let’s assume we’re a sophisticated block builder, and our block simulations are measured in nanoseconds. Taking the same example, we can consider for argument’s sake that all the progressive combinations are built and sent over the wire simultaneously. We can also assume the transactions are the same “size” in bytes.

We would submit the following simultaniously

| block bid 1 | block bid 2 | block bid 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tx | effective gas tip | tx | effective gas tip | tx | effective gas tip | ||

| tx0 | 0.1 | tx0 | 0.1 | tx0 | 0.01 | ||

| tx1 | 0.05 | tx1 | 0.05 | ||||

| tx2 | 0.02 |

Even though they are sent at the same time, they will arrive at the relay at different points in time, even assuming the best-case speed of light scenario. That could be enough time to close the auction before accepting your most profitable block; it arrived too late. We still end up in the same scenario; some transactions are not in the block when they could be. Again, we have sacrificed block space utilisation for priority fee profit.

When we think about mev in this context, the problem becomes even more compounded and skewed. You could easily see a scenario where a single transaction is worth more to a block builder than all other transactions combined. The block builder could end up landing that block with just a single transaction in it (perhaps it’s already happened).

Block Builder Endgame

All block builders will eventually end up at this place, where they rationally fire as many bids as possible at relays. The winning bid may be a block full of transactions and priority fees, a single transaction with high mev or high priority fees, or, more likely, some combination of the two where valid lower priority fee transactions get ignored. In the current PBS design, during periods of high volatility, pressure will be placed on users to increase their priority fees using guesswork because of the opaque pricing structure.

In short, priority gas auctions are now priority fee auctions without visibility of the floor price.

This is not the result of malicious behaviour or malpractice. This emergent pattern is simply the result of the rules of the game.

Example

Let’s take a look at an example 19317738 was ~43% full. At that point in time using block-builder-mempool we estimate that there were 189 valid pending transactions in the public mempool totaling ~13108 Gwei.

Take a look at transactions.csv for the full list.

According to ethernow the following transaction 0xc5d13b765a88b7a96d0dca75441a761b9414e7ab4b98edaf2524fb60888b53fe entered the mempool at 08:33:41.433 UTC, 3 minutes before the block was built. There is no reason for this transaction not to be included in that block, the transaction max fee per gas was 50.25 Gwei, well below the block base fee of ~35.9 Gwei. The transaction was a simple transfer, meaning it would not interfere with other trading strategies. The max priority fee per gas is low ~0.0007 Gwei so the block builder would only receive ~16 Gwei for their efforts (assuming they take it all), but it it is above zero!

| Transaction | |

|---|---|

| Hash | 0xc5d13b765a88b7a96d0dca75441a761b9414e7ab4b98edaf2524fb60888b53fe |

| Max Fee Per Gas | 50255024024 |

| Max Priority Fee Per Gas | 782994 |

| Gas Limit | 21000 |

| Block | |

|---|---|

| Number | 19317738 |

| Base Fee Per Gas | 35993952264 |

| Block Transaction | |

|---|---|

| Block Number | 19317738 |

| Tx Hash | 0xc5d13b765a88b7a96d0dca75441a761b9414e7ab4b98edaf2524fb60888b53fe |

| Gas Used | 21000 |

| Base Fee Burnt | 35993952264 |

| Priority Fee | 16442874000 |

Again, I do not belive this to be malicious. It’s just what you need to do to play the game and win.

Some ideas to punish defectors

We need to design a better game and punish defectors. I believe the protocol’s aim in this regard should be to maximise the use of block space. Blocks should be filled with as many transactions as possible; we’ve demonstrated that this is not happening because ‘lighter’ blocks transmit quicker and arrive at relays faster or, more pertinently, can be sent later. We should explore ways of levelling the playing field between ‘lightweight’ and ‘heavy’ blocks. That is, we should make it more profitable for a block builder to send a heavy block instead of a light one.

Target Gas

One option is to extend the thinking around EIP 1559. The EIP introduced the notion of a ‘target gas’. When the block is above the target gas, the base fee goes up; when it’s below, it goes down. You could have something similar that incentivises block builders to fill up blocks. You could have something fixed like you currently do or dynamically adjust it based on the previous block gas used.

Padding

Let’s say we have a target gas used that blocks must consume to be valid. The block builder must fill the block with valid transactions. If there aren’t enough transactions in the mempool, then the block should be padded with noise. The goal here is to slow the block down (over the wire) so that it is on equal terms with a block with many transactions.

Alternative MEV Burn

If we don’t like the idea of padding, we could force the proposer to make a payment to a burn address. The block builder must ‘burn’ enough gas to esnure that the target gas used for the block is valid. The goal is to make it more expensive to send ‘lightweight’ blocks.

Conclusion

We must design mechanisms that facilitate the behaviours we want from the system. The first step is recognising that the current system encourages block builder behaviour that is not in the best interests of ethereum. I do not believe there is a way to “solve mev”; however, we can ensure that the externalities of mev do not impact execution quality for other transactions.

Thanks to Ryan Schneider and Simon Brown for early feedback and comments.

References

https://ethresear.ch/t/why-enshrine-proposer-builder-separation-a-viable-path-to-epbs/15710/1

https://ethresear.ch/t/mev-burn-a-simple-design/15590

https://www.slatestarcodexabridged.com/Meditations-On-Moloch